Shaped By & Shaping the World

Although the world traditionally thinks of MIT in terms of scientific and technological innovation, the community channels its zest for invention into all areas of human endeavor. From efforts to mitigate poverty and climate change to expanding the global reach of education, the Institute’s passionate innovators have shaped the world we live in—and are shaping it now.

Research

From MIT’s earliest days in Boston, government support was crucial to its existence. Thanks to the generosity of the state of Massachusetts—and Abraham Lincoln’s federal land grant act—MIT obtained the funds to establish itself and to attract the support of private donors.

When the Institute moved to Cambridge, it quickly proved to be one of the most productive research institutions in the world, thanks in large part to government support. Renowned for its defense advances during the two world wars, the Institute expanded its innovative reach and its impact via collaboration with government agencies, relationships that deepened in the post-war era. MIT researchers developed inertial guidance systems for the Apollo space program, pioneered high-speed photography, achieved the first chemical synthesis of penicillin, and built the magnetic core memory that made digital computers possible—all with the support of federal grants.

Today, the Department of Defense and the Department of Health and Human Services fund the greatest percentage of MIT research. The Department of Energy and NASA are not far behind. The National Science Foundation (NSF) has sponsored some of MIT’s most influential research projects—including the LIGO Scientific Collaboration that enabled scientists at MIT and Caltech to observe gravitational waves—one of the great discoveries of our time.

More

-

MIT Office of the Provost, “Institutional Research FY2015”

Global responsibility: J-PAL’s Education sector seeks to improve access to and delivery of high-quality schooling at the primary and post-primary levels through research on issues like pedagogy, teacher training, incentives (for children, for teachers, for families), school governance, early childhood development, and information and communications technology. Photo: Aude Guerrucci

Global Responsibility

With students from 90 countries, MIT is very much plugged in to the wider world. The Institute sees global engagement as a core element of its commitment to improve life on Earth. For generations, MIT students and faculty have collaborated with educators, governments, and marketplace partners across the globe to develop solutions to issues thwarting the advancement of civilization. In MIT’s earliest days in Cambridge, Institute scientists and engineers focused on technological innovation—like the invention of the wind tunnel. During World War II and the Cold War, considerable focus shifted to defense work.

For the last half century, increasing effort has been invested in projects that aid the betterment of the human condition. The MIT Energy Initiative (MITEI) links science, innovation, and policy to transform the world’s energy systems. MIT President Susan Hockfield commissioned the report by the Energy Research Council that led to the founding of MITEI, which is now one of the world’s leading research centers for work on climate change and smart energy. In another sphere, the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) has mobilized 131 professors from 40+ universities to combat poverty. In fact, at this point in time, there’s at least one group at MIT dedicated to most global dilemmas.

More

Artificial Intelligence

In 1945, Vannevar Bush, who had served as dean of engineering at MIT before the war, published a visionary article in The Atlantic Monthly predicting, in remarkable detail, advances in information technology. “As We May Think,” inspired scientists and engineers around the world to realize aspects of Bush’s vision, leading to key advances in computer science. Bush himself had famously advanced the differential analyzer, a mechanical analogue computer.

Computer-related research at MIT began to heat up at midcentury when war work, to some extent, receded as a priority. In the late 1940s, as part of Project Whirlwind, Jay Forrester developed magnetic core memory—essential to early computers and, until recently, to complex computers like those on NASA’s space shuttle. In 1958, John McCarthy and Marvin Minsky launched the MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab with a mere $50,000, propelling it into one of the most influential robotics hothouses in the world. In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee, director of MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), invented the World Wide Web. Today, more than 50 groups on campus are advancing the digital age through sophisticated robotics, computer systems, and theory.

More

-

Listen to the Institute’s artificial intelligence pioneers talk about the development of AI at MIT

-

Vannevar Bush, “As We May Think,” The Atlantic Monthly (July 1945)

-

Stefanie Chiou, Craig Music, Kara Sprague, Rebekah Wahba, “A Marriage of Convenience: The Founding of the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory” (AI Lab: December 2001)

Anti-War Protests

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, anti-war demonstrators frequently protested the Institute’s ongoing defense research. In 1968, a student group offered sanctuary to AWOL soldier Mike O’Conner, creating a sleep-in in the Sala de Puerto Rico as they waited for federal authorities to apprehend him. Many faculty and administrators welcomed O’Conner, offering him a dorm room at MIT. Noam Chomsky and Sylvain Bromberger even talked about creating a “Mike Scholarship” for AWOL soldiers. O’Conner was arrested without violence nearly two weeks after students took him in.

President Howard Johnson, a mediator by profession, was skilled in his dealings with protesters—in part, because he was sympathetic to their concerns. MIT actually had more names on Nixon’s “enemies list” (including Jerome Wiesner, Johnson’s successor) than any other organization. In 1969, Johnson convened a cross-Institute panel of students, faculty, alumni, and administrators to review MIT’s defense activities. The committee met for 36 days straight. A few months later, the Institute divested itself of the Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, where missile guidance systems were being developed (Draper Labs was also developing guidance systems for the Apollo missions). Another significant outcome of anti-war tumult was the cofounding of the Union of Concerned Scientists at MIT by professor and Nobel laureate Henry Kendall.

More

-

Dennis Hevesi, “Howard W. Johnson, President of MIT During Vietnam War Protests, Dies at 88,” The New York Times (December 18, 2009)

-

Kathryn Jeffreys, “This week in MIT History,” The Tech (November 2, 1999)

Photo: Over 100 students gathered to protest Dow Chemical Co. in 1967; Tech File photo

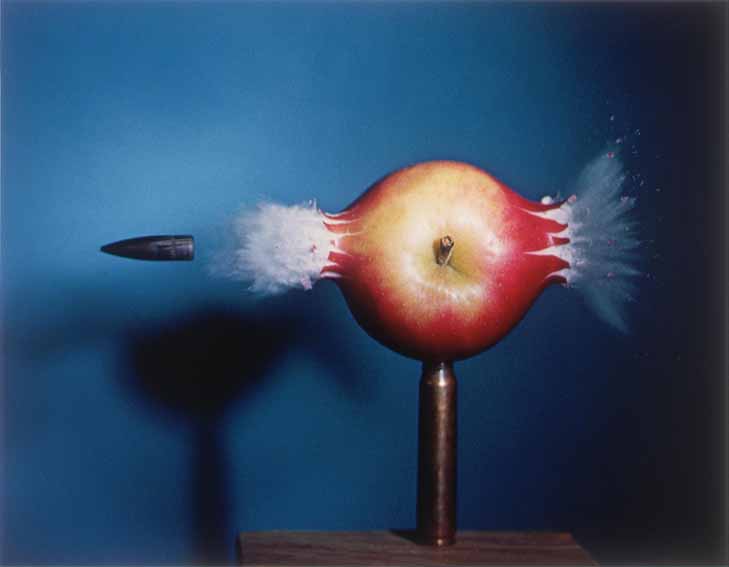

Harold Edgerton's 1964 image of a bullet piercing an apple is one of his most famous images. Learn more about Edgerton and his techniques.

©2010 MIT. Courtesy of MIT Museum

World War II

In September 1940, MIT President Karl Taylor Compton was summoned to a society party in Washington. The soiree was actually a front for a top secret meeting with British officials who were intent on enlisting the help of American scientists in developing a tool that would detect enemy craft by air or sea. The MIT Radiation Lab was born at that meeting, the lab named to imply atomic research rather that its true mission—the development of radar. Soon the lab, established in the hastily constructed Building 20, was employing nearly 4,000 people, including 20% of all US physicists. The effort produced single antenna radar, crucial to the winning of the war.

MIT alumnus Vannevar Bush, whom Compton had once named dean of the MIT School of Engineering, now headed American defense R&D. Bush funded several other vital war-time advances at the Institute, including inertial navigation at Charles Stark Draper’s instrumentation lab, a digital computer for flight simulations under Project Whirlwind, and high-speed high-altitude photography in Harold Edgerton’s strobe lab.

More

-

Watch MIT leaders talk about the Institute’s research activities during World War II

-

Deborah Douglas, “MIT and War,” Becoming MIT: Moments of Decision, ed. David Kaiser (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2010)

-

James R. Killian, The Education of a College President (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1985)

-

Joyce Bedi, “MIT and World War II: Ingredients for a Hot Spot of Invention,” Prototype (May 2010)

MIT OpenCourseWare (OCW)

MIT’s mission, since it moved to Cambridge a century ago, has been to make a significant difference in the quality of life on Earth. The Institute’s invention of OpenCourseWare (OCW) has given it one of its most profound opportunities for impact. A revolutionary approach to sharing educational resources, OCW launched in April of 2001. The site presents, freely and openly, core academic content from nearly all of MIT’s undergraduate and graduate courses; at last count, more than 2,300 were available online. Most offer homework problems, exams, and lecture notes. Others include interactive web demonstrations, streaming video lectures, and textbooks.

More than two million visitors from across the globe visit the site every month. Educators use OCW to improve courses and curricula. Students use it to supplement coursework. Independent learners use it to tackle some of our world’s most difficult challenges. OCW has inspired a worldwide movement that now includes hundreds of universities sharing materials from more than ten thousand courses.

More